By Greg Clough

George Bernard Shaw described America and England as two nations separated by one language. How would he describe one nation separated by two or more languages?

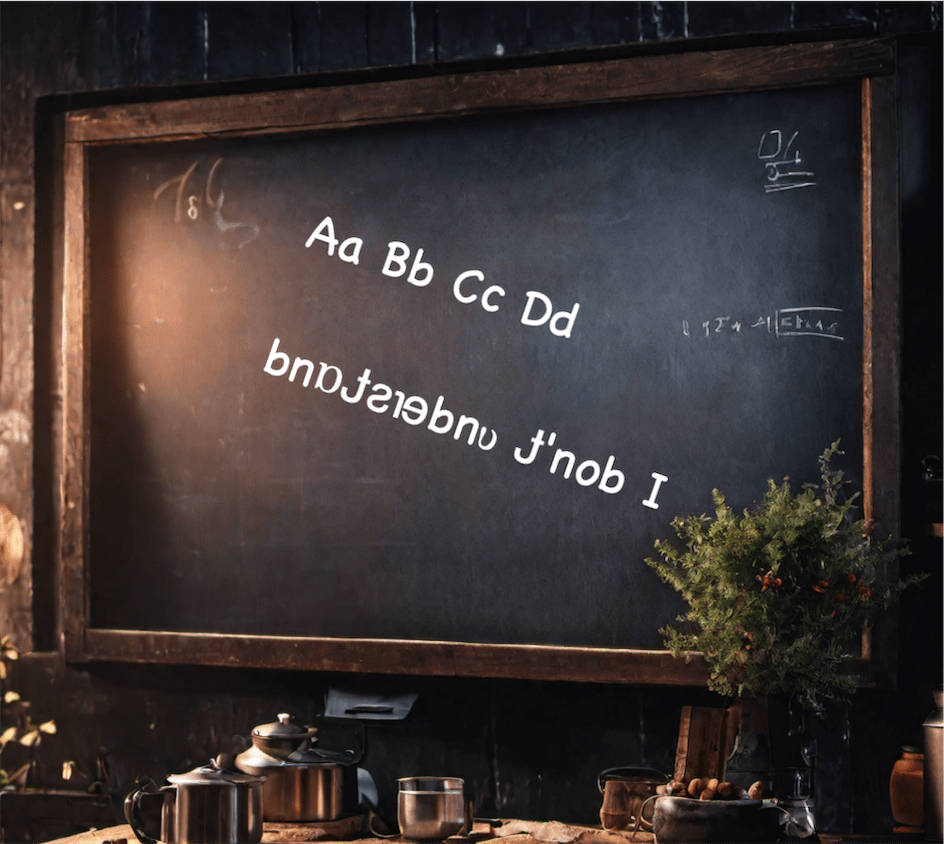

Imagine living in a country that has a national language but you can’t speak it properly. Imagine attending a school where the teachers speak the national language and you don’t really understand. Imagine answering test questions you don’t fully comprehend. Stressful, right?

This disconnect between national languages, languages used in national education systems, and languages spoken at home is not unusual.

In Pakistan, Urdu is the main language of instruction, but only about 7% of the population speak Urdu as their first language. In Ethiopia, Amharic is the main language used in schools but is the first language of only 30% of Ethiopians. Similarly, in the Philippines, Tagalog is spoken in schools, but only 20% of Filipinos speak it as their mother tongue.

Certainly, large percentages of the population in such countries have some level of familiarity with their national language. Still, it is a second language. Depending on the level of understanding, this presents challenges for students and teachers.

Students may have difficulty understanding courses and textbooks if they are unfamiliar with the language used in schools, leading to poor academic performance and high dropout rates.

Often, young learners are challenged by the lack of textbooks in their first tongue, making it hard to study or do homework with mum’s help. Also, curriculum and teaching materials written in the national language may not be culturally relevant to the students’ backgrounds, undermining their interest in learning.

Another major concern is that a disconnect between national, school and home languages can marginalize students who don’t speak the national language fluently, excluding them from educational opportunities and perpetuating inequality.

Teachers face challenges, too. If the national language is their first and only language, they may struggle to communicate complex ideas to students for whom it is not, resulting in misunderstanding and ineffective teaching. And we all know from our own days in the schoolyard that the best teachers are those who build good relationships with their students. Teachers and students may struggle to achieve this if they are not on the same linguistic wavelength.

Teachers need to be innovative, creative and empathetic when teaching a classroom full of students with different skill levels in the national language. Swapping classroom strategies with fellow teachers is a good place to start, as is providing teachers professional development. Naturally, teachers must guide their students with simple words, avoid jargon and understand students’ different vocabulary levels. Incorporating visual aids and real-life examples also enhances understanding for learners.

Teachers need to be innovative when teaching students with different national language skill levels. For example, consider Ajan Souksavanh, a teacher in Lao PDR where only 40% of citizens speak the national language. Using facial and hand gestures for emphasis is another vital tool. A good exponent of using body language is Ajan Souksavanh, a public school teacher from a remote province in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic. As part of her contribution to BEQUAL, a Tetra Tech managed Australia-Lao PDR partnership bringing literacy to disadvantaged school children*, Ajan adapts her teaching to ensure all students understand.

Says Ajan, “I use body language and will explain three to four times the activity”. Ajan also likes using visual aids, saying, “I prepare sets of pictures that will help students learning Lao Language. I make the cards myself, inspired by the textbooks or research in (the) internet. I will also use techniques from the new Lao Language curriculum and some from the Spoken Lao Program. They are very helpful. I especially like the technique ‘listen and practice’. I also use the techniques demonstrated in the teacher development videos to practice and prepare my lessons”.

Clearly, the disconnect between national languages, languages of instruction, and home languages poses challenges for students and teachers. This disconnect may lead to subpar academic achievement, exclusion, and impede efficient instruction. But, as Ajan demonstrates, the challenges are not insurmountable. Innovative strategies like gestures, visual aids, and real-world examples are essential to connecting with all students, regardless of their differing backgrounds. Closing linguistic disparities and giving all kids relevant learning opportunities through inclusive teaching is crucial for developing and developed countries alike. After all, the children learning their ABCs today will be their countries’ leaders tomorrow.

#MultilingualEducation

#InclusiveTeaching

#LanguageBarrier

#EmpoweringDiverseLearners